Did you know that twinning is rare and highly risky in large-bodied Mammals like elephants and giraffes?

Introduction

In the animal kingdom, birth is a delicate dance of genetics, survival, and maternal investment. Delivering one offspring at a time is the biological standard for most mammals. But what happens when nature gives you two?

Twinning in mammals, the birth of two offspring from a single pregnancy, ranges from routine in some species to near miraculous in others. From humans to elephants, twinning has captivated scientists and storytellers alike. But why do some mammals rarely bear twins? And what does twinning reveal about survival strategies in the wild?

This article takes a deep dive into the world of mammalian twinning. It uncovers the biological logic behind single births, explores why twinning can be a dangerous anomaly in certain species, and highlights extraordinary cases of twin births observed in the wild, especially across East Africa, where the world’s most iconic mammals roam.

Why This Matters to the Curious Traveler

Understanding twin births in mammals isn’t just an academic exercise, it deepens one’s appreciation for the complexity and beauty of nature. A single elephant calf trotting behind its mother is a wonder in itself; two calves of the same age following the same mother? That’s a phenomenon worth pausing for.

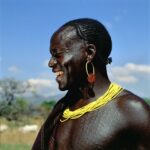

This kind of knowledge enriches every wildlife encounter. Whether observing giraffes in acacia woodlands or tracking rhinos through thick bush, knowing how rare and risky a twin birth is, brings context and reverence to the moment.

What You’ll Discover in the Pages Ahead

In the coming sections, we will explore:

- The biological mechanisms behind twinning.

- Species where twin births are common and evolutionary favored.

- Species where twin births are extremely rare and often risky.

- Fascinating, real-life twin birth stories involving elephants, giraffes, and more.

- The implications of twinning for wildlife conservation and survival.

- How tourists and nature lovers can view these events through a richer, more informed lens.

This article offers a unique perspective on one of nature’s most fascinating reproductive flukes. Twinning is more than just two animals born at once; it’s a lens through which we can better understand how species balance reproduction, survival, and the future of their kind.

The Science of Twinning: How and Why It Happens in Mammals

Twinning in mammals begins at the most fundamental level, conception. Understanding why it occurs in some species and not in others hinges on two biological pathways:

1. Monozygotic (Identical) Twinning

- Mechanism: A single embryo splits into two genetically identical individuals, usually during the first week after fertilization.

- Incidence: Spontaneous and rare, occurring in humans at roughly 0.3–0.4% per pregnancy, and similarly low but observed in some non-human primates like chimpanzees (∼0.4%)

- Evolutionary Role: When found in wild species, it’s often regarded as a fluke rather than an adaptation.

2. Dizygotic (Fraternal) Twinning

- Mechanism: Two separate ova are released and independently fertilized, resulting in genetically distinct siblings.

- Influencing Factors: Multiple ovulations are key here, influenced by genetics, maternal age, nutrition, and hormonal levels, particularly FSH, seen in both humans and chimpanzees.

- Adaptive Significance: Twinning maximizes reproductive output in species with short lifespans or high juvenile mortality.

Why Some Species Twin Easily and Others Don’t

- Species with Frequent Twinning

- Callitrichine Primates (e.g., marmosets and tamarins)

These small monkeys habitually produce twins or triplets. Genetic adaptations in ovulation and growth-regulating genes (e.g. GDF9, BMP15) enable regular multiple births. Cooperative breeding, where fathers and older siblings assist, is the evolutionary strategy that makes this sustainable. - Domestic Ungulates (e.g., sheep, cattle)

Certain breeds display moderate twinning rates (cattle: 1–5%, sheep higher), driven by selective breeding and environmental factors like nutrition and age. - Small Mammals (rodents, pigs):

Rapid reproduction and high mortality favor larger litters; twinning is commonplace and rarely risky.

Species Where Twins Are Rare and Risky

- Large-bodied, Long-lived Mammals (elephants, giraffes, rhinos, whales, hippos)

These species typically invest everything in one offspring.- Slow reproductive cycles and huge neonatal demands make twins nearly impossible. The energy cost for the mother doubles, often fatally so.

- Even rare monozygotic twins found in elephants in reserves highlight how twinning can deviate from wild norms.

- Precocial Large Herbivores (like moose and antelope)

These animals occasionally twin, typically when the maternal condition is high. For example, older female moose in prime condition may produce twins, and gender ratios skew toward males, reflecting their health.

Maternal Condition: A Key Trigger

In many species, twinning is condition-dependent:

- Moose Studies: Older, well-nourished females have higher twinning rates and more balanced sex ratios.

- Saiga Antelope: Females in peak condition can produce twins, even triplets, investing up to 17% of their body weight in offspring.

- Callitrichines: Maternal weight correlates with litter size; cooperative help allows high reproductive output.

Evolutionary Trade-Offs

Evolution shapes reproductive strategies through competing pressures:

- Quality vs. Quantity: If offspring survival is low, producing more increases odds of genetic continuation. If survival per offspring is high, focusing on one is safer.

- Maternal Investment Constraints: Large mammals can’t biologically support twins due to gestational and postnatal resource limits.

- Social Adaptations: Species with cooperative caregiving can support multiples; twinning is likely to penalize mother and offspring where that structure lacks.

Mammals Where Twinning/Multiples Is the Norm

In nature, reproductive success is a game of numbers, and some mammals have mastered the art of producing multiple offspring at once. For these species, twinning and even birthing triplets or more is not a fluke but a finely tuned survival strategy. Unlike elephants or giraffes that can barely afford to raise more than one calf at a time, these animals are biologically and behaviorally equipped for high-output reproduction. Let’s explore the species where twinning is not just common, but necessary for survival.

Rodents

Rodents, including mice, rats, squirrels, and voles, are among the most reproductively efficient mammals on earth. A single mouse can give birth to litters of 6 to 12 pups and reproduce multiple times per year.

- Why so many? Rodents have short lifespans, high predation rates, and rapid sexual maturity. Producing large litters increases the odds that at least some offspring will survive.

- Biological readiness: Their reproductive anatomy, especially in females, is geared toward supporting multiple embryos. The uterus has two horns, and ovulation often releases several eggs at once.

- Developmental stage at birth: Rodents are typically altricial, meaning the young are born underdeveloped and dependent, which reduces the prenatal investment compared to large, precocial mammals.

Pigs

Domestic pigs (Sus scrofa domesticus) are another example of mammals where twinning is not only normal but a minimum expectation.

- Typical litter size: 8 to 14 piglets, sometimes more.

- Reproductive design: Sows ovulate multiple eggs per cycle, up to 20, and have elongated uterine horns to accommodate the large litters.

- Evolutionary logic: Like rodents, pigs face natural threats (disease, environmental instability) that make high birth output essential. In the wild, even with parental care, not all piglets will make it.

Interestingly, the same litter-bearing trend extends to wild boars and warthogs, species tourists may spot in savanna landscapes across East Africa. A mother warthog with six piglets is not a rare sight, and those young ones will be weaned rapidly to make way for the next cycle.

Callitrichine Primates: Cooperative Parenting Makes Twinning Possible

In the forests of South America live the callitrichine monkeys, marmosets and tamarins, who provide one of the rare examples of primates where twinning is the norm.

- Natural twinners: Almost all births result in twins, and triplets are not uncommon.

- The catch? High maternal investment would be unsustainable without help. In these species, fathers and older siblings take on a large portion of infant care, carrying, grooming, and guarding the young.

- Evolutionary compromise: These monkeys have relatively small bodies and can’t produce much milk. But the shared care system offsets the burden, allowing more than one infant to thrive.

Though callitrichines aren’t found in Africa, they provide a crucial comparison: twinning works best in species that either invest very little per offspring (rodents) or have a social support system that spreads the burden (primates like marmosets).

Small Carnivores and Insectivores

Meerkats, mongooses, foxes, and some bat species also fall into this category. These animals often live in cooperative groups and may give birth to multiple young at once, usually in safe, secluded dens.

- Meerkats and mongooses: Known for their social structures, these animals benefit from communal care, with babysitting, guarding, and feeding shared among group members.

- Bats: Though many species give birth to one pup per year, some like the Mexican free-tailed bat can bear twins. Colonies of thousands ensure some level of collective safety and temperature regulation, which makes raising more than one pup feasible.

Common Traits in Frequent Twinners

Species where twinning or litter-bearing is common tend to share the following features:

- Short gestation periods and fast sexual maturity.

- High juvenile mortality, requiring multiple births to ensure survival of some offspring.

- Social behaviors or ecological niches that make rapid population growth advantageous.

- Anatomical adaptations, like bifurcated uteruses, that can sustain multiple embryos simultaneously.

Rare and Risky Twin Births in Large Mammals

In many of the world’s most iconic and long-lived mammals, twinning is not a reproductive strategy, it’s an anomaly. For species like elephants, giraffes, rhinoceroses, and cetaceans, a twin pregnancy poses enormous risks. Let’s explore the biological, ecological, and survival implications when twins occur among these rarest of large mammals.

Elephants

Elephants, both African and Asian, have the longest gestation of all mammals (18–22 months) and pour immense resources into each calf. A twin pregnancy pressures the mother’s capacity:

- Twinning frequency:

- Asian elephants: ~0.5–1%—for example, three twin births in 258 pregnancies in Tamil Nadu camps (1.16%).

- African elephants: ~0.07% in Amboseli (2 twins in 2,687 births), but up to 1% in Tarangire.

- Survival outcomes: Twins born in reserves may survive with human aid; in the wild, survival is unpredictable.

- Biological limitations: Elephants have two mammary glands, supporting two calves divides milk supply and attention. As one expert noted, large-body mammals “have only two teats and adequately nourish a single offspring at a time.”

- Social support: Elephant herds practice allomothering, other females assist in care, but even that may not be enough to offset the demands of twin calves.

Giraffes

Giraffes typically give birth to a single precocial calf, capable of standing within hours of birth, a dramatic requirement given their height. Twinning here is extraordinarily rare, documented only a handful of times, including viral cases:

- Notable incidents:

Twin giraffes born in Nairobi (year unspecified) and 2013 in Texas ranches made international headlines due to their improbability. - Risk factors: Twins in giraffes are often lighter and more vulnerable to predation. The mother risks injury due to awkward birthing positions and weight constraints.

- Birth site: Death or abandonment may result if one calf is too weak to stand, critical in the first moments of life.

Rhinoceroses

Rhino calves are solitary by nature, consuming enormous maternal resources:

- Twinning extremely rare: There are virtually no verified wild rhino twin births. A few captive or semi-wild cases, like Truda, the southern white rhino calf born in Texas, are exceptions.

- Gestation and care: Rhinoceroses gestate for 15–16 months. The mother typically focuses on a single calf, teaching it survival skills and defending it fiercely.

- Ecological impact: Should twins be born, the risk of one starving, being abandoned, or dying is very high, both in the wild and in managed care.

Cetaceans and Hippos

- Whales & Dolphins: Giving birth under water adds complications, newborns must surface to breathe immediately. Twins increase drowning risk and reduce bonding time, making survival extremely slim.

- Hippopotamuses: Rare twin births are seldom recorded. Hippo calves begin nursing hours after birth, but the mother remains in water for long stretches, making simultaneous care difficult.

Why Twinning in These Mammals Is So Risky

- Physical constraints: Large, precocial calves demand room in utero, startle maternal systems, and challenge birthing mechanics.

- Behavioral limits: Twins require simultaneous care, impossible in species adapted for single offspring.

- Ecological stakes: In predator-heavy habitats and harsh environments, one calf may perish while the other struggles, or both may be abandoned.

- Evolutionary pressure: Natural selection favors single births in these species; twinning remains a rare vestige rather than an adaptive norm.

Real-World Cases of Twin Births In Large Mammals

- Samburu, Kenya (2022): Female elephant Bora gave birth to male and female twins—only the second such recorded event in the region. The event made global headlines and conservation efforts raced to monitor their survival academia.edu+3bbc.com+3aa.com.tr+3.

- (2022): An Asian elephant gave birth near a water-filled crater. The mother struggled, and the calves nearly drowned before being rescued downtoearth.org.in.

- Captive Twins: Rhino twins in Texas and giraffe twins in ranches showcase that even with human intervention, twin births remain rare and fraught with developmental risks.

Documented Twin Births and Their Aftermath

When twins are born to large mammals in their natural habitats, the event is nothing short of extraordinary. These rare occurrences capture the attention of wildlife scientists, tourists, and conservation groups alike, serving as both joyous milestones and sobering reminders of nature’s fragility.

1. Elephant Twins in Samburu, Kenya (2022–2024)

In January 2022, in the heart of Kenya’s Samburu National Reserve, guides from Elephant Watch Camp documented a pair of elephant twins born to a female named Bora kxel.com+7savetheelephants.org+7janewynyard.com+7. The calves, a male and a female, were roughly one day old when first sighted 850wftl.com+5savetheelephants.org+5janewynyard.com+5.

Chances of Survival:

Twinning in elephants occur in approximately 1% of births. In Samburu, the previous set of twins born in 2006 did not survive past a few days. The survival of Bora’s twins, despite a severe drought, was deemed unlikely, but resilience prevailed. By March, both calves were confirmed alive and healthy.

Conservation Response:

The event triggered vigilant monitoring by Save the Elephants and local lion-protection teams. The drought eased by April, abundant grasses returned, and tracking collars were deployed to keep watch.

Outcome:

Unfortunately, while the male twin continued to thrive, his sister passed away later that same year, a stark testament to the unpredictable realities of twin rearing in challenging environments.

2. Another Set of Elephant Twins: Alto’s Story (2023)

Remarkably, in November 2023, another elephant, Alto of the “Clouds” family in Samburu, gave birth to twin daughters 850wftl.com+7cbsnews.com+7standardmedia.co.ke+7. This marked the second twin occurrence in the reserve within just under two years.

Context & Conservation:

Following heavy rains and lush vegetation, conservationists held cautious optimism. The herd’s cooperative nature suggested increased chances for survival, and early sightings confirmed both calves feeding robustly.

Significance:

Twin births of this magnitude, twice in as many years, are virtually unheard of. The pattern suggests strong maternal condition and exceptional herd dynamics, raising hope for future success.

3. Giraffe Twins

Although no giraffe twin births have been recorded in East Africa’s protected areas like Samburu, there are notable global instances:

- Texas and Kenya/captive cases: Twin giraffes born in Texas ranches and Nairobi’s national park have made international news reddit.com+12standardmedia.co.ke+12cbsnews.com+12.

Challenges Faced:

The major risk lies in immediate post-birth vulnerability. These calves must stand quickly or fall prey to predation. In many observed cases, the calves lagged, endangering their survival. No documented wild twin giraffe births in East Africa have been confirmed to survive successfully.

4. Rhino and Other Large Mammal Twins

Twin births in rhinoceroses and other large mammals are practically unknown in the wild. A few captive occurrences, such as a southern white rhino calf named Truda in Texas, highlight how even with human care, twins remain biologically challenging.

Why Twins Rarely Thrive:

These twin birth cases offer more than just sensational news, they yield critical insights:

- Maternal Health Matters: Bora and Alto’s twin births were likely driven by exceptional maternal condition, rainfall, and herd support.

- Role of Herd Dynamics: Elephant social systems, like protective behavior, allomothering, and food-sharing, play critical roles in survival.

- Monitoring Pays Off: Tracking twins via collars and camera-traps enables timely interventions, such as medical assistance or anti-poaching measures.

- Ecosystem Signals: Twin births may signal broader environmental health, when resources and rainfall are sufficient for increased reproductive outcomes.

What This Means for You, the Observer

If you’re on safari and glimpse two calves close to the same mother, recognize it as a once-in-a-lifetime event, not common lore. These moments deserve respectful distance, quiet reverence, and an understanding of the natural fragility they represent.

Postnatal Challenges of Twin Mammals in the Wild

Even when twins are successfully born to large mammals, their journey has only just begun. Unlike smaller mammals that instinctively birth and nurture litters, large mammals face significant physiological and ecological constraints that often lead to stark postnatal outcomes: one twin survives, the other dies. Here below we xplores what happens after birth, and why postnatal survival for twins in the wild is a delicate balance between maternal capacity, sibling rivalry, and environmental stability.

1. Maternal Investment, Built for One, Not Two

Large mammals like elephants, giraffes, and rhinos are biologically tuned to invest deeply in a single offspring:

- Lactation demands: Elephant mothers produce up to 11.4 liters of milk per day, rich in fats and proteins, but designed for one calf. Dividing that between two results in nutritional compromise for both.

- Nursing mechanics: In species with only two teats (e.g., elephants, rhinos, hippos), competition for access begins early. The stronger twin often dominates, nursing more frequently, while the weaker may lag in growth.

- Duration of care: Elephants nurse for up to 3–5 years. A mother must balance weaning one calf while nourishing the other, something not naturally sustainable for twins in the wild.

In giraffes, where calves must rise within 30 minutes to avoid predation, the weaker of a twin pair may never make it to the first feed. In rhinos, mothers are known to travel long distances shortly after birth, something a weaker twin may not survive.

2. Sibling Competition

In species where twins occur but resources are limited, sibling rivalry can turn deadly. While this is well-documented in birds like eagles, it manifests subtly in mammals:

- Competition for milk: The stronger twin, often slightly larger at birth, latches more quickly and more effectively. Over time, this advantage compounds, leading to malnourishment or even starvation for the other.

- Thermal regulation: In the first weeks of life, calves rely heavily on maternal body heat and shade. Being edged out by a sibling can expose the weaker twin to cold or sun stress.

- Movement and mobility: Mothers of large species are always on the move. Twins must keep up. The slower twin risks being left behind, especially in herds that do not slow down for the weak.

Even in relatively controlled environments, such as in sanctuaries or game reserves, twins born to large mammals exhibit this natural inequality, one often becomes visibly more robust within a matter of weeks.

3. Social Structures, Can the Herd Help?

Some hope lies in the social behavior of species like elephants, which practice allomothering, where sisters, aunts, or other females help care for calves:

- Shared caretaking: In elephants, older females may allow both twins to nurse or guide a struggling calf toward water or shade.

- Protective behavior: The herd creates a physical barrier around calves when predators or threats appear. Twins benefit from this collective shielding, if both remain close.

- Teaching moments: Social learning is key in species like elephants. Twins exposed equally to older herd members may have a better chance of picking up survival cues.

However, even this system has limits. In dry seasons or during migration, herds may need to move fast, and only the fittest calves, often just one of the twins, can keep pace.

4. External Pressures: Drought, Predators, and Human Disturbance

Postnatal survival is never just about biology; it’s shaped by external forces too:

- Drought: As seen in Samburu during Bora’s twin birth, scarce food and water weaken the mother and reduce milk supply, making it harder to support two calves.

- Predators: Lions, hyenas, and leopards target young calves, especially those that lag. A single distracted moment can cost a twin its life.

- Poaching and human encroachment: Disturbances cause herds to flee or change routes. Twins that are not strong enough may be abandoned during hasty retreats.

Even in well-managed conservation areas, the margin between survival and loss remains slim for twin calves. That’s why so few stories of twins in the wild have happy endings, and why when both calves survive, it becomes global news.

Conservation Efforts and Scientific Responses

When twin births occur among large mammals in the wild, conservationists face a complex challenge: should they intervene or let nature take its course? While nature favors single births for many large mammals, today’s conservationists are increasingly called to balance natural processes with active wildlife management, especially in the face of climate change, habitat loss, and dwindling population numbers. In this section, we explore how wildlife experts respond to twin births, and what their actions reveal about our evolving relationship with the wild.

1. Monitoring Twin Births in Real Time

One of the most effective tools in modern conservation is the use of tracking collars and GPS tagging, particularly in elephant and giraffe populations. When a mother gives birth to twins:

- Collars provide daily movement data, showing whether she lags (suggesting health issues) or travels steadily with both calves.

- Satellite-linked alerts allow rangers to locate the animals quickly if needed.

- In places like Samburu and Tarangire, this data was instrumental in tracking Bora and Alto’s twins, ensuring they remained within proximity of food and water sources.

This kind of surveillance is minimally invasive yet provides critical insight into calf movement, maternal behavior, and the timing of key life events like first nursing and calf bonding.

2. Emergency Interventions: When to Step In

Intervening in nature is a sensitive decision. Conservationists weigh several factors before deciding to help:

- Condition of the weaker twin: If severely dehydrated or separated from the herd, rescuers may administer fluids or reunite it with its mother.

- Maternal distress: If the mother is struggling, injured or exhausted, she may not be able to support two calves. Supplemental feeding may be considered for one twin.

- Environmental severity: During drought or fire, twins are often at high risk. Emergency shelters or shaded feeding stations may be installed temporarily.

Notable Example:

In India’s Bandipur Reserve, forest rangers had to help two elephant twins escape from a muddy waterhole where they were stuck after birth. The calves were cleaned and monitored before being guided back to their mother, who surprisingly accepted both without issue.

These rare interventions have a narrow window of success. The longer a calf is away from the mother, the lower its chance of acceptance back into the herd.

3. Supplemental Feeding and Calf Shelters

In rescue centers and national parks, emergency calf care units have been used sparingly to support orphans and weak twins:

- Specialized milk formula replicates elephant or rhino milk and is often administered by trained caretakers wearing clothing scented with dung or earth to avoid imprinting.

- Soft release programs eventually return calves to semi-wild areas, sometimes integrating them into established herds.

Though extremely rare for twins, these methods offer a safety net in emergencies. For instance, in the Sheldrick Wildlife Trust in Kenya, orphaned calves have been hand-raised and later reintroduced into Tsavo’s wild herds, showing that with effort and time, second chances are possible.

4. Protection from Predators and Poaching

Twin births, especially in high-risk zones, can attract the unwanted attention of predators and poachers:

- Dedicated patrols are often deployed in parks like Amboseli, Samburu, and Queen Elizabeth to monitor the vulnerable family group.

- Tourist guides are trained to avoid approaching twins, giving them space and alerting authorities if one is separated or injured.

- Community rangers work with nearby villages to report sightings or potential threats to newly born twins.

These measures ensure that while the wild retains its raw essence, vulnerable animals, especially rare twin calves, get the best chance possible at survival.

5. Scientific Value of Twin Data

Every twin birth presents an opportunity for research that could improve our understanding of mammalian reproduction and ecosystem health:

- Hormonal analysis of the mother’s blood or feces can indicate the conditions that led to twinning, such as nutrient spikes or hormonal imbalances.

- DNA sampling helps determine if twins are fraternal or identical, providing insight into reproductive anomalies or success rates.

- Long-term tracking of twin survival rates contributes to predictive models used in wildlife population management.

In many cases, scientists work closely with local rangers and even tourism operators, who often make the first sightings of twin calves. This collaborative approach enriches conservation science while fostering local stewardship.

6. Tourism’s Role in Twin Survival

Ironically, the presence of responsible tourism can improve twin survival chances:

- Tourists act as informal reporters, notifying rangers of twin sightings.

- Their presence can deter poachers, especially in high-traffic reserves.

- Revenues from safari visits often fund patrol teams, veterinary units, and monitoring technology.

However, the opposite is also true: unregulated tourism can put calves in danger. Chasing elephants with cars for a better photo or crowding a giraffe mother can cause stress that leads to abandonment. That’s why ecotourism, when done ethically, is a crucial ally of conservation.

The Future of Twin Births

There’s something deeply symbolic about the birth of twins in the animal kingdom, especially when it occurs in species biologically inclined to avoid it. These rare dual arrivals bring hope, curiosity, and challenge all in one breath. For wildlife lovers, conservationists, and safari travelers alike, twinning forces us to confront the delicate balance between what nature intends and what modern stewardship makes possible.

1. What Twin Births Reveal About Ecosystem Health

Twin births in large mammals may be harbingers of abundance or stress, depending on context:

- In good years—marked by rainfall, plenty of forage, and minimal disturbance, some mammals may stretch their reproductive limits.

- In stressful periods, however, twinning may result from hormonal imbalance or environmental disruption, and often ends in loss.

This duality means that documenting twin births, and their outcomes, is more than just a feel-good story. It’s a window into how ecosystems function, how females allocate resources, and how social structures support or hinder reproductive success.

In effect, twin births are natural indicators, helping scientists gauge the biological resilience of species and the pressures they face.

2. The Place of Tourists in This Conversation

As a traveler on safari, your role extends beyond sightseeing. Every sighting of a rare event, like a pair of newborns trailing an elephant matriarch, is a moment of shared responsibility:

- To observe, not intrude, giving space ensures the natural bond between mother and calves isn’t disrupted.

- To ask questions, engage with guides and rangers about what you see. Many local experts carry years of knowledge about the area’s herds and birth histories.

- To spread awareness, photos and stories shared online can inspire interest in conservation, but they must be shared with accuracy, context, and care.

Your experience becomes part of the broader conservation narrative. It helps humanize wildlife, fund anti-poaching efforts, and encourage other travelers to respect the wild.

3. The Scientific and Emotional Weight of Rarity

While multiple births are common in rodents, carnivores, and primates, in large wild mammals, especially elephants, giraffes, and rhinos, twins are a biological anomaly. And in that anomaly lies meaning:

- It reflects the limits of maternal endurance, how much one body can provide.

- It demonstrates the cooperation or failure of social groups, do others step in, or does the mother struggle alone?

- It challenges our assumptions about wilderness stability. If more twins begin to survive, is it a sign of ecological recovery, or just a rare burst in a volatile trend?

Emotionally, these births strike a chord. They offer a glimpse of vulnerability in creatures we often see as indomitable. A twin calf, leaning gently against its mother’s leg, evokes something ancient and universal: the drive to live, to be seen, and to be protected.

4. How We Can Help

If twinning among wild mammals is to be better understood and better supported, several steps are critical:

- Continued funding for research on reproductive physiology in elephants, rhinos, and giraffes.

- Better documentation and transparency from wildlife authorities, keeping birth records, health data, and survival timelines accessible.

- Expansion of ecotourism models that emphasize education and ethics, not just entertainment.

- Policy integration, where governments acknowledge that rare reproductive events have scientific value and should be supported by conservation frameworks.

These efforts aren’t just about saving a rare calf, they’re about deepening our understanding of nature’s blueprint and embracing the complexity of life in its wildest form.

Final Reflections

Across East Africa, the sighting of twin calves, be they elephant, giraffe, or even warthog, is always met with hushed excitement. It’s more than a biological oddity. It’s a story of nature pushing its limits, of survival against the odds, and of motherhood at its most raw.

For travelers, researchers, and conservationists alike, these stories remind us that wildlife is not a static picture; it is an unfolding drama. One that deserves our attention, our respect, and our protection.

Let the twin births remind us of the wild’s unpredictability and let our curiosity be matched by humility. In the silence of a savanna evening, with two tiny trunks raised beside their mother’s, we are reminded: nature never stops surprising us.