Series 2

OUTSOURCED PARENTING-BROOD PARASITISM IN BIRDS

THE CUCKOO (CUCULIDAE FAMILY)

When people hear the term brood parasitism, the cuckoo is usually the first bird that comes to mind, and with good reason. Belonging to the Cuculidae family, cuckoos are among the most studied and specialized brood parasites in the world. While not all cuckoos are parasitic, many members of this group have perfected the art of laying their eggs in the nests of unsuspecting foster parents, creating one of the most fascinating evolutionary strategies in the avian kingdom.

Key Parasitic Species

Some of the best-known parasitic cuckoos include:

- Common cuckoo (Cuculus canorus) – Found across Europe and Asia

- African emerald cuckoo (Chrysococcyx cupreus) – Widespread in sub-Saharan Africa

- Dideric cuckoo (Chrysococcyx caprius) – Common in Africa, especially near water sources

- Great spotted cuckoo (Clamator glandarius) – Found in southern Europe, North Africa, and parts of the Middle East

These species, despite their differences in range and appearance, share a common trick: laying their eggs in the nests of other birds, often smaller species.

Habitat and Distribution

Cuckoos are globally distributed, with parasitic species found throughout Europe, Asia, and Africa. Each species has evolved to suit its region:

- The Common cuckoo migrates from Europe to sub-Saharan Africa during winter.

- The Emerald cuckoo is a forest dweller, commonly found in tropical and subtropical African woodlands.

- The Dideric cuckoo thrives near rivers and wetlands, following weaver birds, which are frequent hosts.

Cuckoos prefer areas rich in insect life, especially caterpillars, their primary food source.

Parasitic cuckoos are solitary. Once grown, a cuckoo chick leaves the foster nest and lives alone. Despite being raised by another species, it instinctively knows to seek out mates of its own kind and replicate the same parasitic behavior it never witnessed. This is one of the most fascinating biological mysteries and may be explained by imprinting at the genetic level or cues from its migratory path.

Diet and Feeding

Cuckoos are mainly insectivorous, and they are particularly fond of hairy caterpillars, many of which other birds avoid. These caterpillars often contain toxins or are covered with irritating hairs, but cuckoos have developed digestive systems capable of neutralizing them. They also feed on grasshoppers, beetles, and sometimes small lizards or snails.

As chicks, cuckoos are entirely dependent on their host parents, who work tirelessly to feed a chick often much larger than themselves.

How parasitism works in Cuckoos

The female cuckoo is an expert spy and strategist. Here’s how the deception unfolds:

- Host Selection: Each female cuckoo belongs to a gentes, a genetic line that specializes in a particular host species. For instance, one female might always target reed warblers, while another prefers pipits. This choice is passed maternally and ensures egg mimicry.

- Egg Mimicry: Through evolution, the cuckoo has developed eggs that closely resemble those of its chosen host species in color, size, and speckling. This reduces the chance of detection and rejection.

- Timing is Everything: The female cuckoo monitors the host nest and waits for the host bird to lay its eggs. Then, in a quick swoop that takes mere seconds, she lays her egg, sometimes removing one of the host’s eggs in the process.

- Hatch and Dominate: Cuckoo eggs usually hatch faster than the host’s. The chick, blind and naked, instinctively pushes the host’s eggs or chicks out of the nest. This behavior is not learned; it is inborn. From then on, the host bird raises the lone intruder, feeding it tirelessly, unaware that it is raising a stranger.

Mating and Reproduction

Cuckoos do not form long-term pair bonds. Males are territorial during breeding seasons and attract females through loud, distinct calls (the “cuck-oo” call, which is famous across Europe). After mating, the female lays between 15 to 25 eggs in a single season, often one per nest. Since she doesn’t incubate or feed her young, she’s free to roam and find multiple nests to parasitize.

Interestingly, females of the same gentes tend to avoid each other’s territories, reducing the chances of two cuckoo eggs ending up in the same nest, which would be disastrous since cuckoo chicks are usually aggressive to any competition.

Migration Patterns

The common cuckoo is a long-distance migrant. After being raised in Europe, it flies to central and southern Africa, on its own, with no guidance from adult cuckoos. It then returns to Europe in spring to breed. Scientists track this remarkable journey using satellite tags.

African species like the Dideric cuckoo are generally partial migrants, moving within regions in response to rainfall and food availability, especially where hosts like weavers and bulbuls are nesting.

Fascinating Facts

- The common cuckoo’s call is one of the most recognized in Europe, and it has even inspired the cuckoo clock.

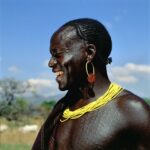

- In Uganda, the African emerald cuckoo’s vibrant green feathers make it one of the most visually stunning parasitic birds.

- Cuckoo chicks have been observed making “begging calls” that mimic an entire brood of chicks, tricking foster parents into bringing more food.

Conclusion in the form of a Human Analogy

Imagine if a stranger snuck a baby into your house while you were out, and when you came home, you started raising that baby—feeding it, protecting it, even giving up food for it, without ever realizing it wasn’t yours. That’s what host birds experience. While funny in theory, in nature it’s a deadly serious survival game, and the cuckoo plays it exceptionally well.