The Ik Tribe: Uganda’s Indigenous, Forgotten Tribe

The Ik tribe primarily inhabits the Kaabong district in northeastern Uganda, east of Kidepo Valley National Park, in the sub-counties of Kamion, Timu, and Morungole. This area borders South Sudan to the northwest, Kenya to the northeast, and the Moroto district to the southeast. With an estimated population of only 14,000 (6,500 males and 7,500 females) according to the 2014 national census, the Ik are one of Uganda’s smallest ethnic groups.

Their name “Ik” loosely translates to “head of migration” or “the first to migrate here,” reflecting their belief that they were the original inhabitants of the Karamoja region before the arrival of other, larger Nilotic pastoralist tribes.

Origin of the Ik Tribe

Origin of the Ik Tribe

Information about the Ik’s origins is scarce, relying largely on oral traditions shared by community elders. Some written accounts exist, such as Colin M. Turnbull’s The Mountain People; however, the remote location of the Ik at the top of Mount Morungole has hindered extensive research and awareness, leaving them relatively unknown to the outside world.

The Ik are believed to have migrated from the Kuliak-speaking people of Ethiopia or further north towards Egypt. According to oral history, during their migration, they split into three groups: the Nyang’i (Ngang’l/Nginyangia), the So (Tepeth), and the Ik. The Ik first settled in Kenya before crossing into Uganda, where they initially occupied the lowlands of the Karamoja region, including the present-day districts of Kaabong, Timu, Kotido, Moroto, Amudat, Napak, and Nakapiripirit.

Originally sustained by hunting and gathering in the Kidepo Valley, the Ik people faced a double displacement: first, the official designation of their land as a game reserve in 1958 and then a national park in 1962; second, relentless violent raids from neighboring pastoralists like the Karamojong. Together, these forces pushed them into mountainous, less fertile terrain.

Forced from their lowland home by these attacks, the Ik retreated to the top of Mount Morungole as a defensive strategy. There, in isolation, they eventually adapted to their new environment, adopting subsistence farming on its slopes.

Language

Although the Ik share some cultural traits, like dress and traditional dances, with neighboring tribes, they maintain a distinct linguistic identity through their language, Teuso (also known as Icêtôt or simply Ik), which is unique to them and unintelligible to surrounding communities.

The Ik language is transmitted not through formal education but as a mother tongue, leading to widespread monolingualism. This is an intentional cultural stance, rooted in the conviction that learning other languages threatens their heritage—a conviction that has historically fueled resistance to languages like English.

Social structure

The Ik people’s distinct social structure—organized around small, fortified villages—developed as a direct adaptation to severe historical pressures. Displaced from their ancestral lands in the Kidepo Valley by the creation of a national park and subjected to persistent raids from neighboring pastoralist groups, they were forced into a defensive, isolated existence on the slopes of Mount Morungole.

In this mountain environment, security shaped their architecture and social life. Their villages are built as defensive compounds, with an outer wall enclosing the settlement.

Inside, smaller, family-based neighborhoods called odoks are further divided into individual, walled household units known as asaks, creating a layered system of protection that emphasizes the self-reliant nuclear family.

This focus on household autonomy, observed during a period of extreme famine, led anthropologist Colin Turnbull to controversially portray the Ik in The Mountain People as loveless and purely individualistic. However, contemporary research presents a more nuanced view, showing the Ik as a resilient society that practices strong cooperation and mutual support when not under extreme duress.

Economic Interaction with Other Tribes

The Ik people originally sustained themselves as hunter-gatherers in the Karamoja region. This livelihood was disrupted in the 1960s when they were displaced from their ancestral lands to create Kidepo Valley National Park. They also faced frequent raids from pastoralist tribes, such as the Karamojong, Dodoth, Turkana, and Pokot, which resulted in the loss of their livestock. Due to these pressures, they retreated to the highlands of Mount Morungole for security.

In this isolated environment, which they inhabit to this day, they practice subsistence farming—a livelihood with deep historical roots that was adapted after their displacement. Their primary agricultural activities include cultivating sorghum, finger millet, and maize as staple crops, supplemented by legumes like beans, soybeans, and leafy greens. A significant secondary activity is beekeeping, which produces honey and beeswax.

These products, along with surplus crops, form the basis of small-scale trade and barter with neighboring groups, often exchanged for items like milk and animal skins. The Ik also sell their produce in nearby centers, such as those in the Kaabong district.

While this agricultural practice ensures their survival, the Ik are not entirely isolated. They maintain connections with neighboring communities through the barter of their produce and by selling goods in local centers.

Leadership

The Ik’s leadership is defined by a decentralized, clan-based structure, where the highest hereditary ceremonial authority is the J’akama Awae, while day-to-day governance and dispute resolution are traditionally handled by councils of respected elders, reflecting their social organization and historical need for security.

Marriage among the Ik

Marriage among the Ik is a complex, conservative institution that preserves their cultural heritage through strict clan exogamy within their 11 foundational clans. The process formalizes alliances between these clans, involving a protracted courtship of manual labor, a bride price paid in subsistence goods like honey, beehives, and farm produce, and culminates in ceremonial rituals like the “capture.” Marriage within one’s own clan is strictly prohibited and believed to invite supernatural calamity. This inward-focused system is further reinforced by an express prohibition against intermarriage with neighboring tribes like the Karamojong and Dodoth, a deliberate maintenance of their distinct language, and incompatible dowry traditions, collectively functioning as a cultural bulwark to prevent dilution of their unique social identity.

Traditional Dances

The Ik tribe has a vibrant tradition of ceremonial dance and drumming, essential for preserving their cultural heritage. They perform specific traditional dances such as the Nyokoroti dance and the Dikwa dance. The Nyokoroti, performed to honor life on Mount Morungole, is a display of strength and endurance where men jump high with women sliding across their legs; if a man falls, it is interpreted as a sign of weakness.

The Dikwa dance, in contrast, is performed during harvests and is accompanied by drumming and the distinctive sound of choorik (jingle bells). Beyond celebration, these energetic dances, accompanied by rhythmic drumming and traditional lyrics, serve a deeper purpose: to honor ancestors, seek blessings, ensure harmony with nature, and pass down ancestral stories and history.

Dress code of the Ik

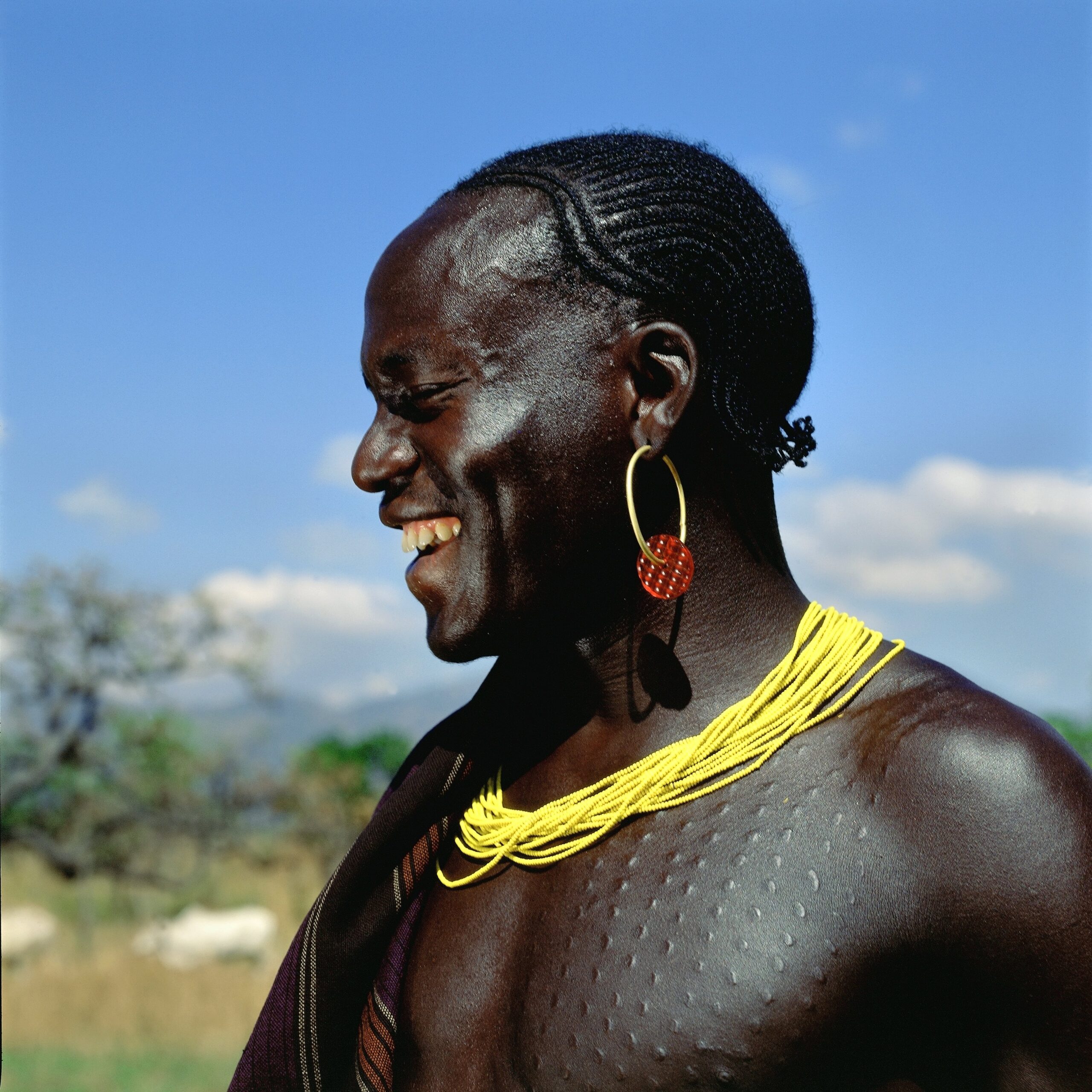

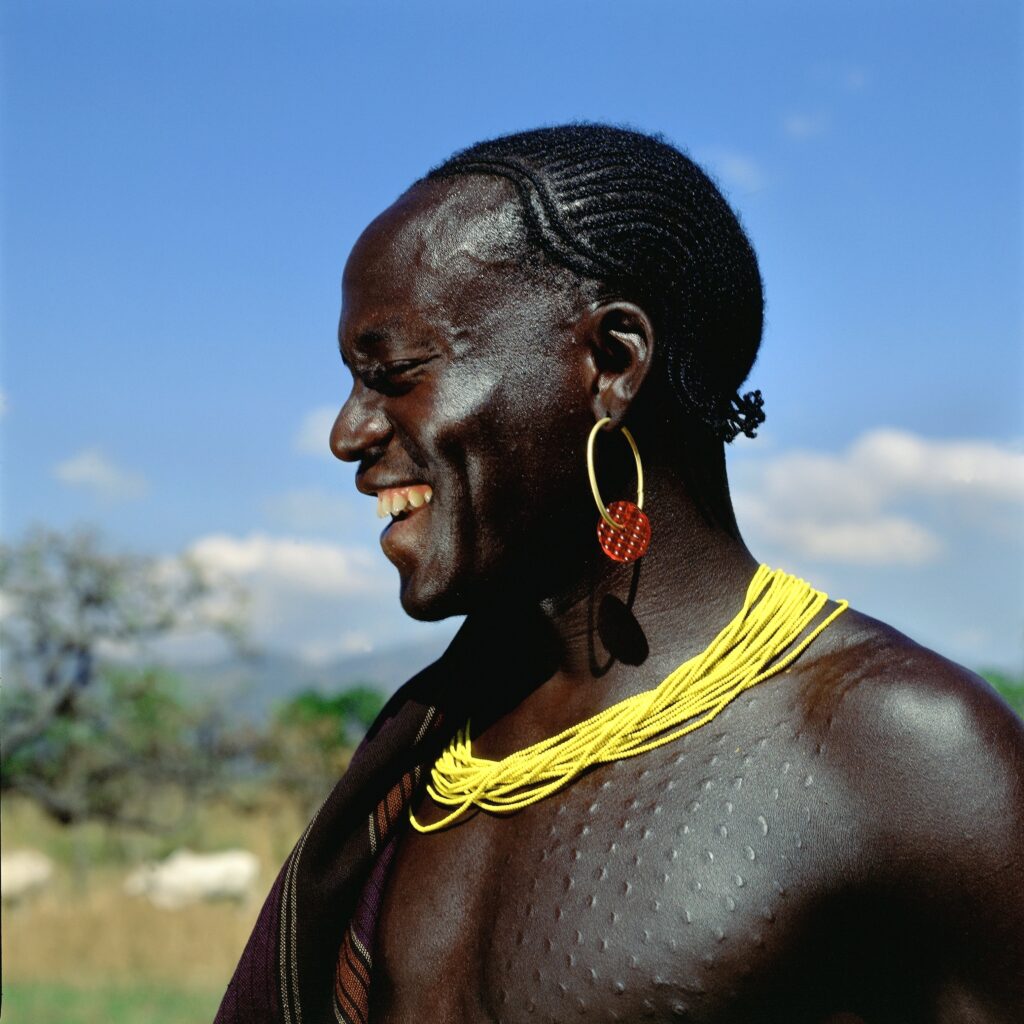

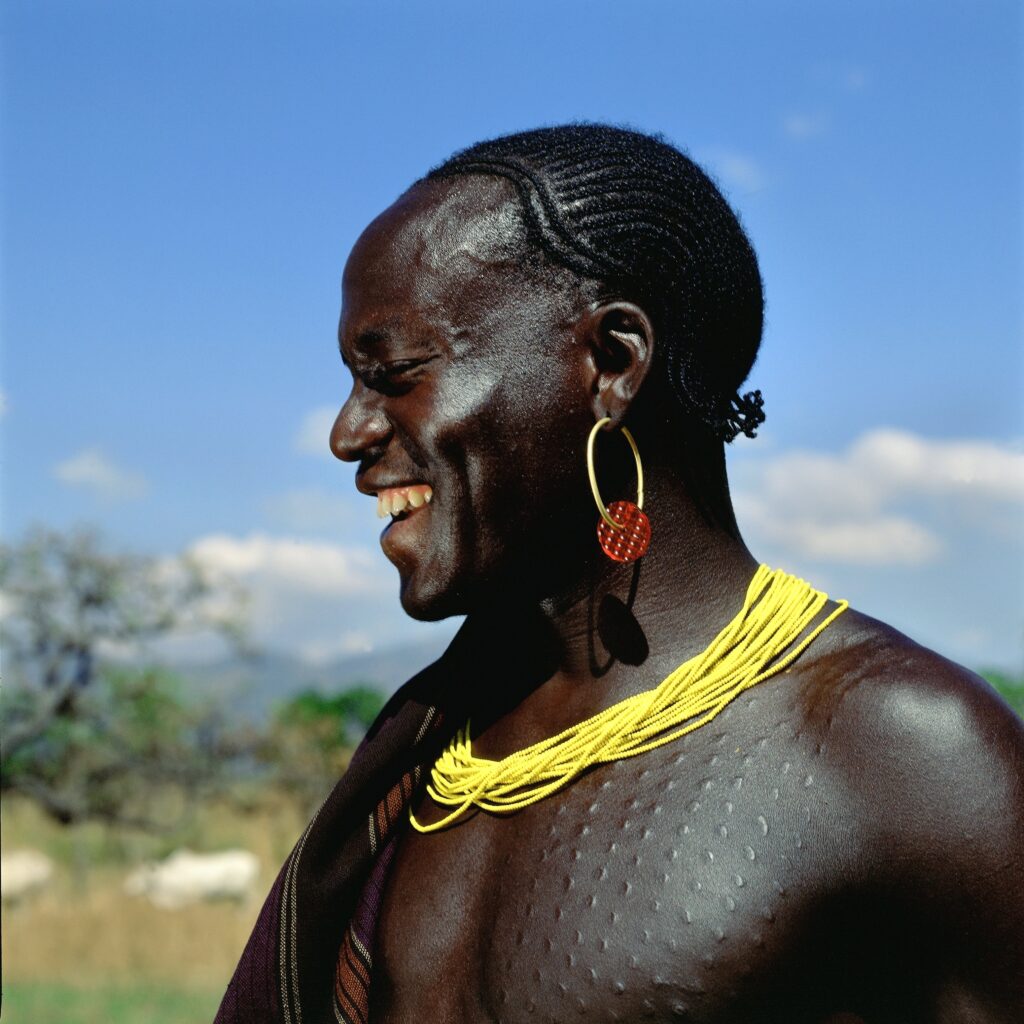

The traditional attire of the Ik is a direct adaptation to their harsh, mountainous environment, historically crafted from animal hides and plant fibers. Men wore loincloths and cloaks for warmth, while women’s skirts and intricate beadwork conveyed important social information such as age, marital status, and standing. However, modern cultural exchange has introduced Western clothing like shirts, trousers, and dresses for everyday wear, reflecting a shift in daily life, while traditional styles are preserved for cultural continuity during special ceremonies.

For important ceremonies, dances, and events, the Ik actively preserve and emphasize their traditional sartorial identity. They creatively incorporate vibrant African fabrics, folding and tying them around the waist, and adorn themselves with heavy, rhythmic beadwork and head coverings to present a distinguished appearance. This deliberate use of traditional materials and adornment for ceremonial purposes stands in direct contrast to the modern, Western-influenced clothing worn in everyday contexts, highlighting a conscious effort to maintain cultural heritage amidst modernization.

Body Marking

The Ik practice of scarification, particularly ornate patterning on women, serves as a culturally significant form of body art for beautification and identification. For women, the markings are considered fashionable, enhance tactile sensitivity, and are ritually believed to prepare them for childbirth. While the practice is often associated with martial achievements in other cultures, for the peaceful Ik, men’s scarification is understood as a symbol of inner strength, courage, and endurance. However, this traditional art form is in decline across many communities, including the Ik, due to modern influences, health concerns, and the adoption of contemporary identification methods.

Challenges facing the Ik

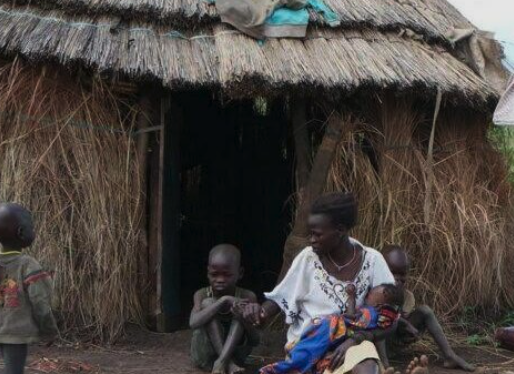

Nestled on the steep slopes of Mount Morungole in northeastern Uganda, the Ik people embody a profound story of cultural resilience, set against a backdrop of persistent and severe challenges. Once displaced from their ancestral lands within the Kidepo Valley National Park, this community of approximately 14,000 individuals faces a confluence of threats that jeopardize their unique identity and well-being.

Their existence is defined by a constant struggle for security and sustenance. As peaceful subsistence farmers, the Ik are recurrent victims of violent raids from more powerful neighboring pastoralist groups, which have persisted for generations. This threat to their lives and food supply is compounded by the unforgiving environment; their hard-won harvests of sorghum and millet are perpetually vulnerable to the droughts that plague the Karamoja region.

Geographical isolation further entrenches their hardship. The Ik’s remote, mountainous homeland creates immense logistical barriers, resulting in critically underdeveloped infrastructure. Access to basic services—healthcare, education, and clean water—remains a significant challenge, a fact starkly highlighted by the stark statistic that only one Ik student is known to have completed secondary education as of 2016. This isolation and marginalization have left them politically voiceless for much of their recent history.

However, the gravest threat may be one of perception. For decades, the world understood the Ik through the controversial and singular lens of anthropologist Colin Turnbull’s 1972 study, The Mountain People, which portrayed them as “loveless” and innately selfish during a period of extreme famine. Modern ethnographic work has thoroughly discredited this portrayal, revealing the Ik to be a people of complex social bonds, generosity, and cultural richness. Yet, the damaging stereotype persists, overshadowing their true nature and their urgent, practical needs.

Therefore, it is imperative to shift the narrative from one of myth to one of meaningful support.

Targeted Development and Protection

The Ugandan government and development partners must prioritize practical interventions in the Kaabong district. This includes improving road access to enable service delivery, investing in sustainable water projects to mitigate drought, and bolstering educational facilities to give Ik youth a future. Equally important is ensuring their physical security from cross-community raids.

Cultural Preservation Through Ethical Engagement

Proactive efforts are needed to document and revitalize the Ik’s unique Nilo-Saharan language and cultural practices before they are eroded by external pressures. This requires support for community-led documentation projects. Furthermore, we encourage a new model of engagement: responsible, ethical tourism. Visitors who come with respect, guided by principles that ensure benefits flow directly to the Ik community, can become vital witnesses. They can experience firsthand the community’s hospitality, verify the inaccuracy of past stereotypes, and help generate sustainable income that values the Ik’s heritage.

Conclusion

The story of the Ik is not one of inevitable decline but of enduring strength in the face of adversity. By replacing outdated myths with informed understanding and channeling our efforts toward tangible support and respectful partnership, we can help ensure that this unique tribe not only survives but thrives for generations to come.